The pioneering GTR Gender Diversity in Trade Finance Survey has revealed what the industry has long needed: data. The results expose both progress and blind spots – and signal the need for continued dialogue, transparency and accountability across the sector.

With diversity, equity and inclusion efforts facing growing pushback around the world, GTR set out to take stock of where the trade finance industry stands. For years, there’s been widespread agreement on the need to bring more women into the sector, elevate them into senior roles and create more inclusive workplace cultures. But without data, there’s no real baseline, making it hard to track progress or pinpoint what’s working.

In the last four months of 2024, GTR conducted the first industry-wide survey on gender diversity in trade finance, designed to offer a snapshot of how gender diversity is experienced – across roles, regions and organisational types – and to serve as a baseline for ongoing benchmarking.

In total, just over 300 respondents from around the world took part in the survey. Approximately three-quarters identified as women, with the majority working in mid to senior-level roles, and around a third based in front-office positions.

The data was geographically diverse, with responses from across continental Europe (29.7%), the UK (24.5%), Asia (16.1%), the Americas (14.5%), Sub-Saharan Africa (10.4%) and the Middle East and North Africa (4.8%).

The vast majority of respondents (85%) were either directly or indirectly involved in providing trade finance services. Most came from banks (45.8%), but there was also strong representation from legal, insurance and other trade finance support functions (20.8%), non-financial commercial organisations involved in trade (28.4%) and non-bank finance providers (4.9%).

To design and interpret the survey, GTR partnered with renowned economist and trade expert Dr Rebecca Harding. She sat down with GTR editorial director Shannon Manders to reflect on the findings and unpack what the data tells us – and just as importantly, what it doesn’t.

GTR: Let’s talk about representation. For years, we’ve been saying women are underrepresented in senior roles in trade finance – was that reflected in the data?

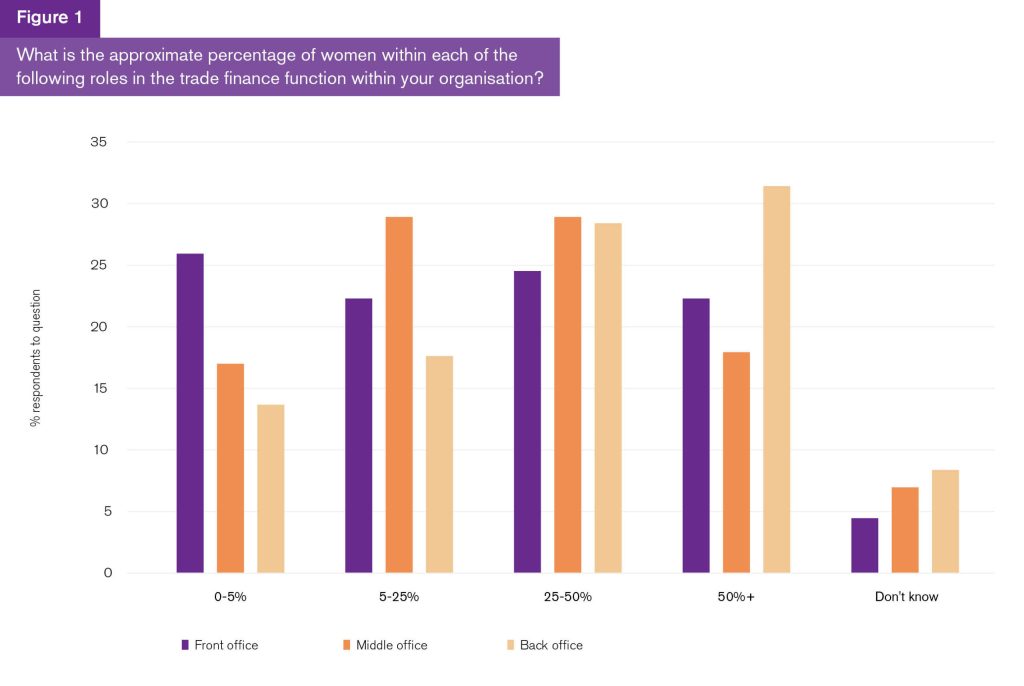

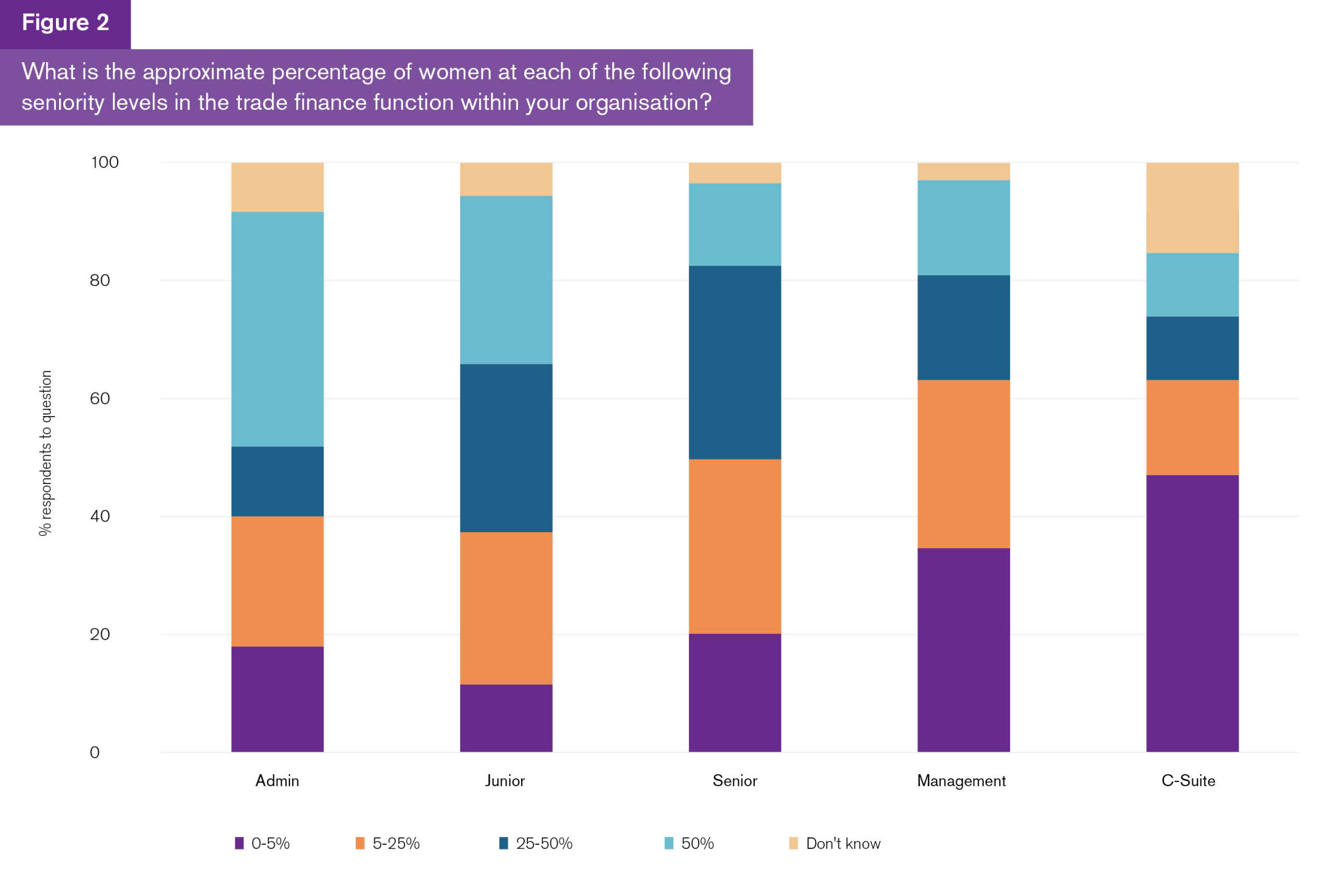

Harding: Yes, absolutely. We had largely middle and senior management responding, so they probably have a good idea of what’s going on in their HR function. What we saw was that women were more represented in junior, back-office and administrative roles. As the data shows, around 95% of the women respondents indicated that they were not in C-suite roles. That aligns with what I found 10 years ago at the British Bankers Association. I remember my boss saying, ‘but women are roughly 50/50, what’s the problem?’ The problem is they’re not in senior positions.

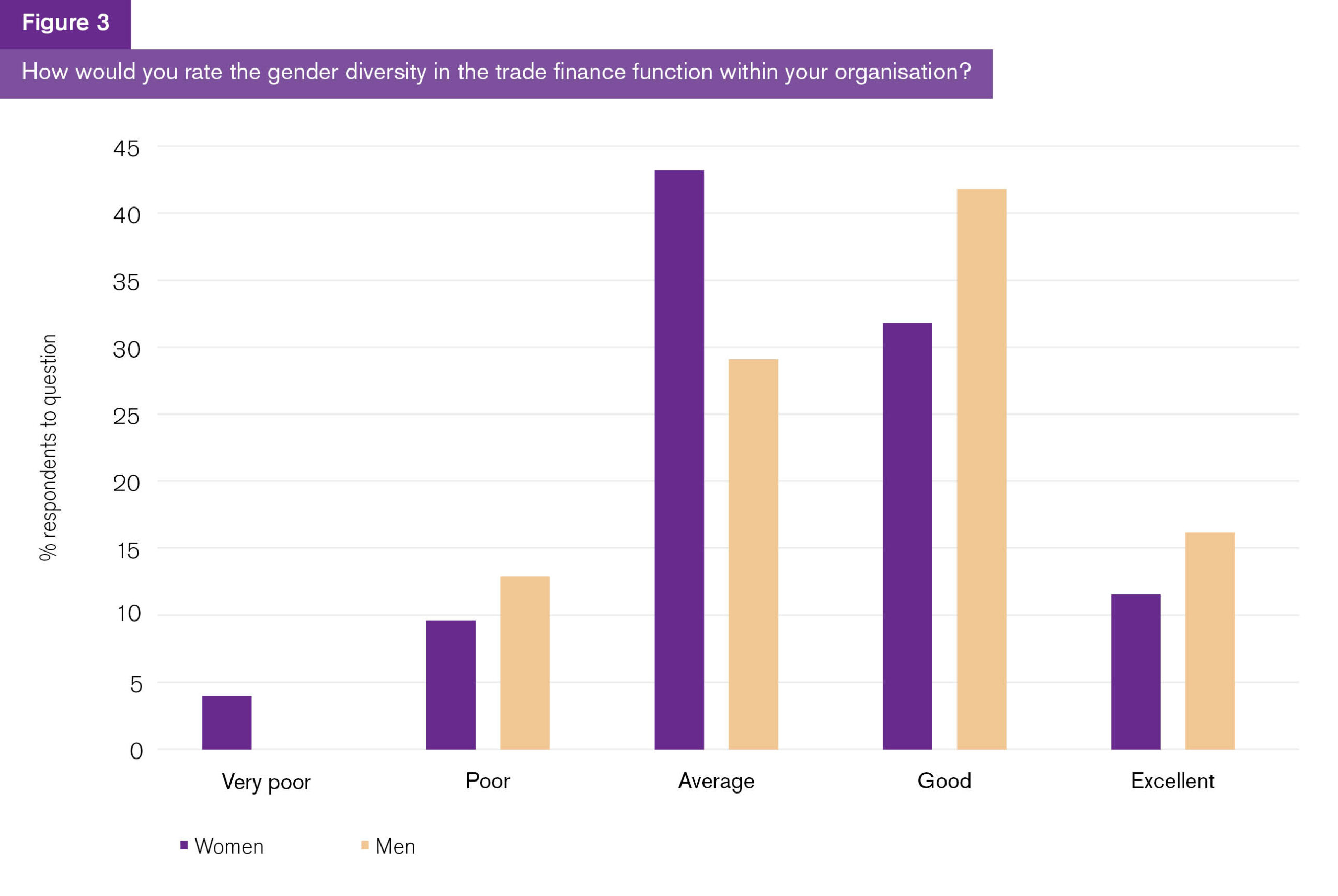

GTR: What did we learn about how respondents rated gender diversity in the trade finance functions of their organisations?

Harding: This chart [figure 3], generally speaking, is a positive one. Both women and men reported relatively favourable views on gender diversity in their organisations. In fact, what’s interesting here is that it suggests that at the time the survey was done, we may have been moving in the right direction. Attitudes toward gender diversity – both within the trade finance function specifically and across organisations more broadly – were largely rated as either ‘average’ or ‘good’.

Women were slightly less positive than men, and that’s a statistically significant result. But broadly speaking, the outlook is encouraging. Organisational type and geography didn’t change that much.

That said, we shouldn’t gloss over the fact that 13.4% of female respondents rated gender diversity as outright poor. That’s a significant proportion – more than one in eight people – who are clearly dissatisfied.

It’s important to note that this data was collected before recent political shifts. On January 20, US President Donald Trump signed an executive order scrapping federal DEI programmes. Do we really think attitudes have improved since then?

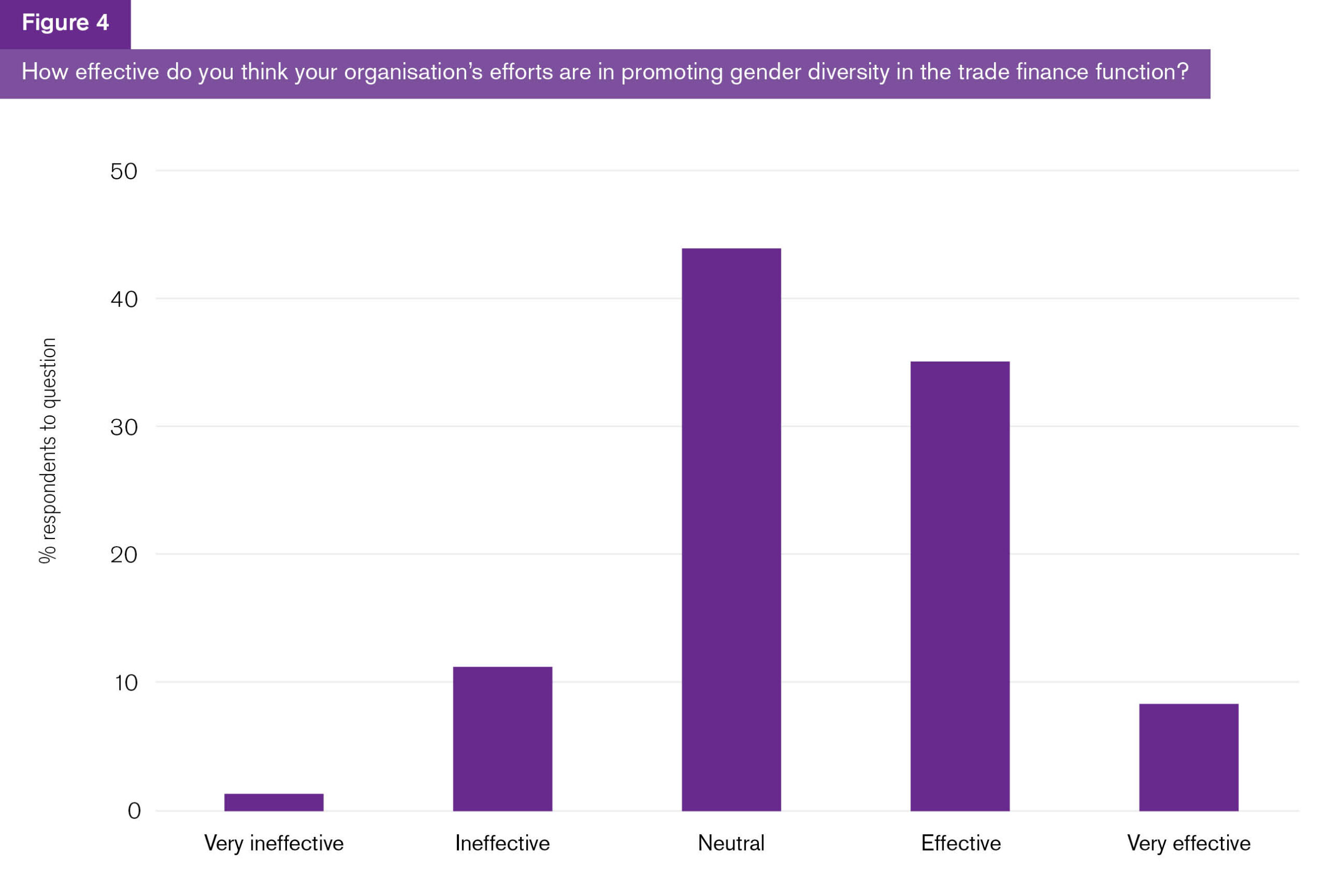

GTR: What did we learn about how respondents view the effectiveness of their organisation’s efforts to promote gender diversity in the trade finance function?

Harding: Altogether, men and women are generally neutral or mildly positive about the ways their organisations are promoting gender diversity in the trade finance function [figure 4].

While the chart shows combined responses, a deeper cut of the data reveals a difference by gender: women in trade finance are more likely to take a neutral view on the effectiveness of their organisation’s gender diversity efforts. Men, meanwhile, tend to be more positive, with a notable number saying those efforts are effective or even very effective.

So there’s a clear gap here, which points to a difference in lived experience. Maybe part of the takeaway is that women need more space or encouragement to share why they’re not experiencing those efforts as strongly. There needs to be more conversation around this.

And it’s not an organisational size issue; we looked at whether small versus large companies showed a difference, and there was no real variation.

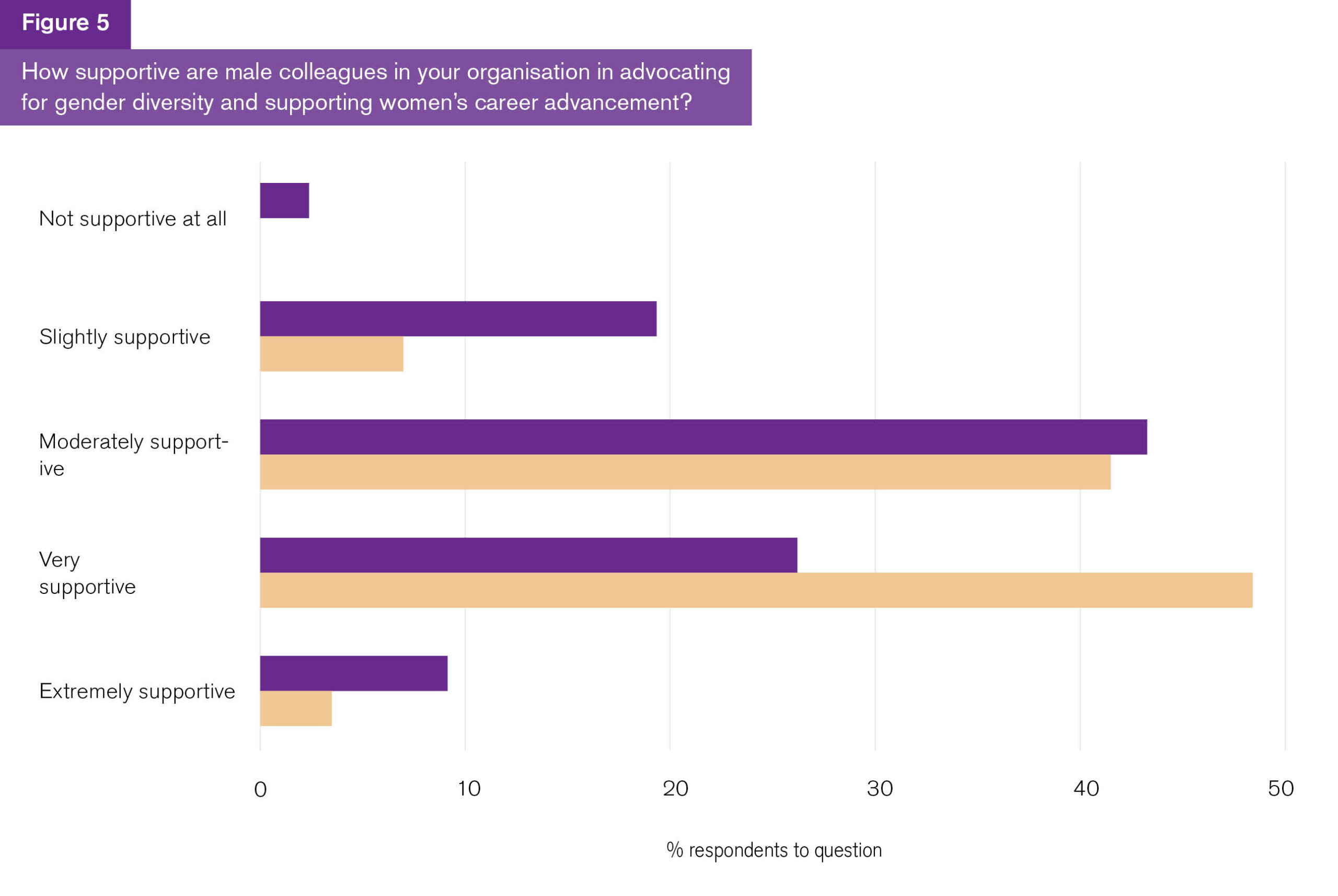

GTR: One thing that stood out is how men rated themselves as being supportive advocates for gender diversity – but women didn’t necessarily agree. What did we see there?

Harding: Men rated themselves very highly as gender diversity advocates. Women did not entirely agree. While the numbers aren’t tragic, there was a mismatch in perception.

The takeaway is that self-perception of allyship doesn’t always translate into felt experience by others.

GTR: We’ve seen a clear shift in the political climate following the election of President Trump: do you think companies are actively retreating from DEI commitments, or is it more of a quiet de-prioritisation?

Harding: I think it’s becoming increasingly explicit. We’re seeing these shifts take root more visibly in the US than elsewhere, but the direction of travel is clear.

The UK government found that in 2019, nearly 5% of all UK workers – roughly one in every 20 – are employed by US-owned companies. That’s an incredibly high number, and it tells us something important – that cultural and policy shifts happening in the US will inevitably begin to shape what happens elsewhere.

There’s very little doubt about that. And to be blunt, if you look at the response – or lack thereof – from corporate America to what’s happening politically, it’s deeply concerning.

Take Project 2025, for example. It’s a proposed overhaul of the federal government, and it’s frankly terrifying. It aims to radically reset the way we think about gender diversity and anything related to what’s being labelled as ‘wokeism’ in the US – essentially, any form of divergent or progressive thinking.

What we’re seeing is a filtering, even a silencing, of conversations around difference and inclusion. I’ve spoken with people in the investment community who say the language is already shifting. There’s now something being described as an ‘America first’ investment policy, where capital stays in the US or must pass national security clearance before it goes abroad. That’s a profound shift.

The language and practices of international business are changing.

What’s equally troubling is the lack of challenge. Even among the tech and social media platforms, where you might expect the diversity and inclusion agenda to be championed, there’s a marked silence. These companies seem to be calculating where their interests lie – and choosing not to speak out.

So while this isn’t directly about gender, it is very much about the broader environment in which these conversations are taking place. And it raises serious questions about what comes next, both for gender diversity and for global business more broadly.

GTR: Is there a risk that the fear of appearing political could silence or dilute conversations about DEI altogether? How do we protect against that?

Harding: The more I look at this, the more urgent it becomes.

We’ve seen how quickly things can change. Within 48 hours of President Trump taking office, there were executive orders rolled out. Since then, there have been more than 200 executive orders, with 36 of them directly related to the economy, the workplace and trade. That’s a significant number. And alongside that, we’ve seen a whole raft of socially focused changes that are fundamentally shifting the tone and priorities of the working world.

It’s easy for people to stay quiet about this. Gender diversity and inclusion can often be dismissed as a ‘nice-to-have’, not something that feels core to the daily grind of business. But as I’ve said repeatedly: it underpins everything we’ve worked towards in the last 40 to 50 years. This isn’t a side issue. The current shift represents a full reversal of decades of progress in workplace equity and representation.

I believe those of us working within European systems have a real responsibility. We can’t turn a blind eye. We need to ask ourselves: what values do we want to uphold? What systems do we want to preserve? For all its flaws, Europe is built on multilateralism – on cooperation, inclusion and dialogue. That foundation is worth protecting. Let’s use it. Let’s keep the conversation going.

The data tells us this work matters. If we ran the same survey in six months, with all the political and cultural shifts underway, would we see the same results? I’m not sure.

And that’s exactly why we need to keep monitoring this. The speed of change demands it. We need a credible, independent voice to say: ‘This matters. We’re watching. We won’t let this slip.’

GTR: In the survey, there was an interesting distinction between where respondents are based and where their company is headquartered in terms of their perception of gender diversity. What did the data show about that difference?

Harding: For me, this was one of the most interesting findings to come out of the data.

If you think about your organisation, it typically operates within a defined regulatory structure – whether that’s based in the UK, the US or elsewhere – and that includes how gender diversity is addressed at a policy level.

But what we found is that people’s perceptions vary depending on where they’re based, not just where the company is headquartered. For example, someone working at a US-headquartered bank but based in another country might have a more positive view of gender diversity than someone interpreting it purely through the lens of headquarters policy.

In other words, while the regulatory frameworks are there – or at least are supposed to be – people’s day-to-day experiences of gender diversity are actually more positive than what the formal structures might suggest. That’s fascinating.

It shows that the behavioural side of it, the culture on the ground, may actually be outpacing the regulatory frameworks. That gap between regulation and lived experience is definitely worth paying attention to.

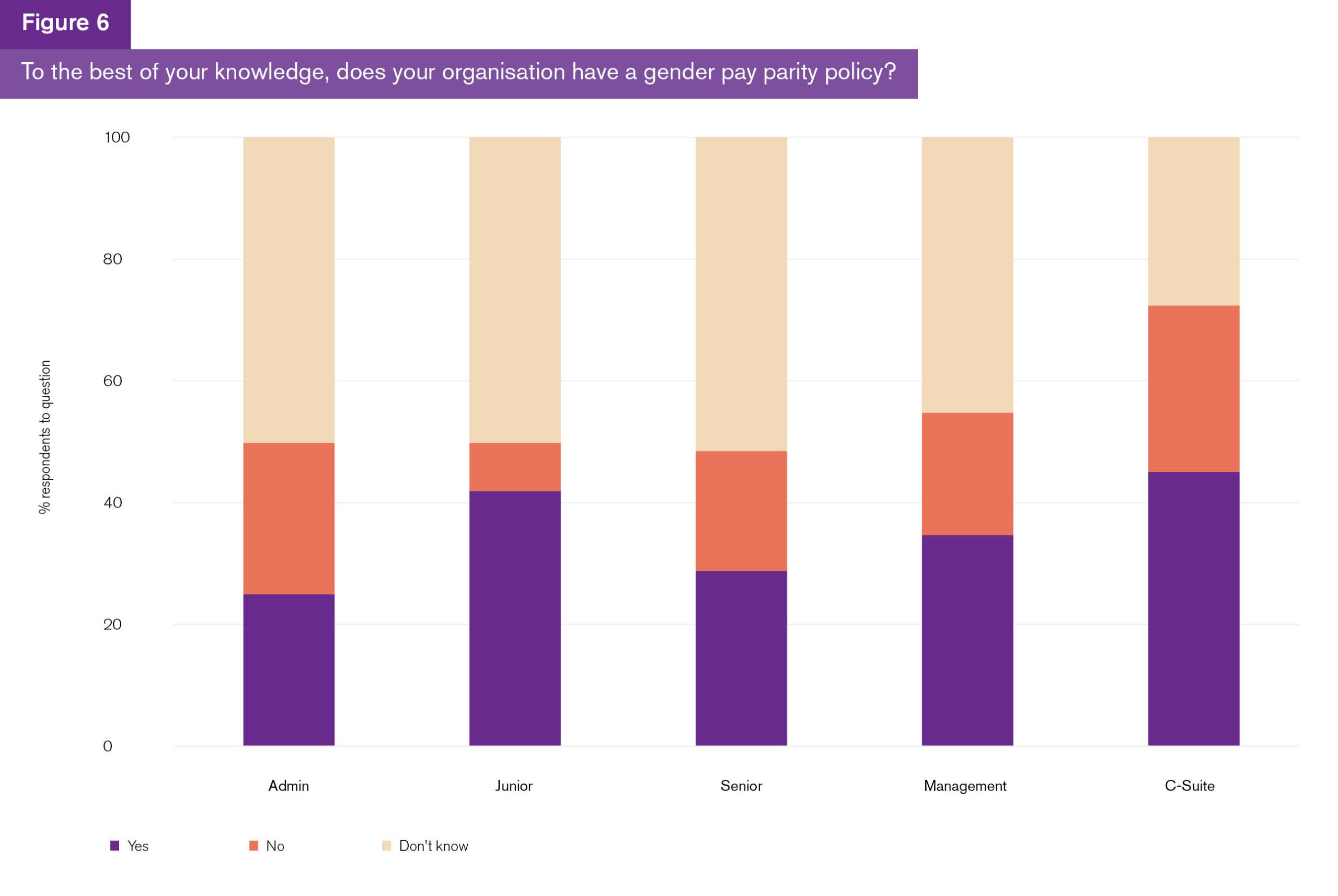

GTR: We asked a number of questions about how organisations apply both internal and external policies or regulations on gender diversity – perhaps most significantly, whether they have a gender pay parity policy. Are people actually aware whether their organisations have such policies?

Harding: This is somewhat depressing, because the number of people who simply didn’t know was very high. Awareness was much more likely if you were in the C-suite or middle management. But across other levels – whether administrative, junior or even some senior roles – that lack of awareness was striking.

This is important. If people aren’t aware of whether a policy exists, they can’t raise it with their line managers or during appraisals. The people in leadership roles who do know, please share that information. Talk to those lower down in the hierarchy.

GTR: If women don’t know whether such a policy exists, what does that mean for their ability to negotiate or advocate for equal pay?

Harding: It becomes a case of negotiating from a place of asymmetric information. If you don’t know, there’s very little you can do. You’d hope organisations would have a clear and explicit gender pay parity policy. But if that message isn’t reaching employees, it undermines their ability to understand where they stand, and to represent themselves fairly.

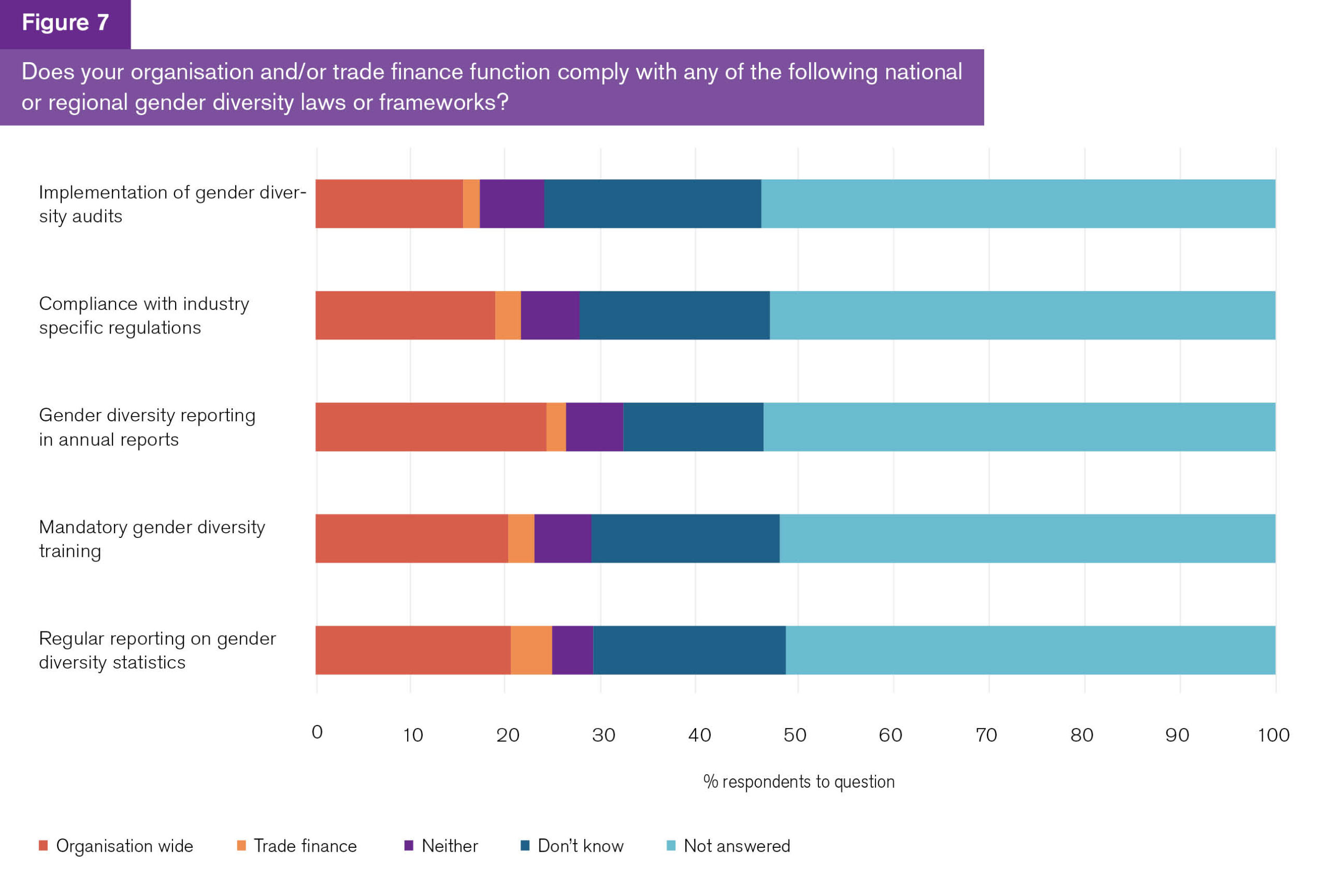

GTR: Beyond pay parity, what did the survey tell us about broader regulatory compliance? Do people actually know whether their organisation meets gender diversity regulations?

Harding: Broadly speaking, people don’t know whether their organisation is complying with existing regulations. It means they’re immediately on the back foot. You need to understand your rights as an individual, whether they relate to learning needs, flexible working or other aspects of workplace inclusion. But if you’re unaware of whether your organisation is even complying with basic diversity regulations, you’re left without the tools to advocate for yourself. You’re operating with incomplete information.

It was interesting to see that only around 20% of respondents said their organisation is complying with diversity policies, and even less so within trade finance, where it appears the function is simply aligning with broader organisation-wide policies, rather than driving its own initiatives.

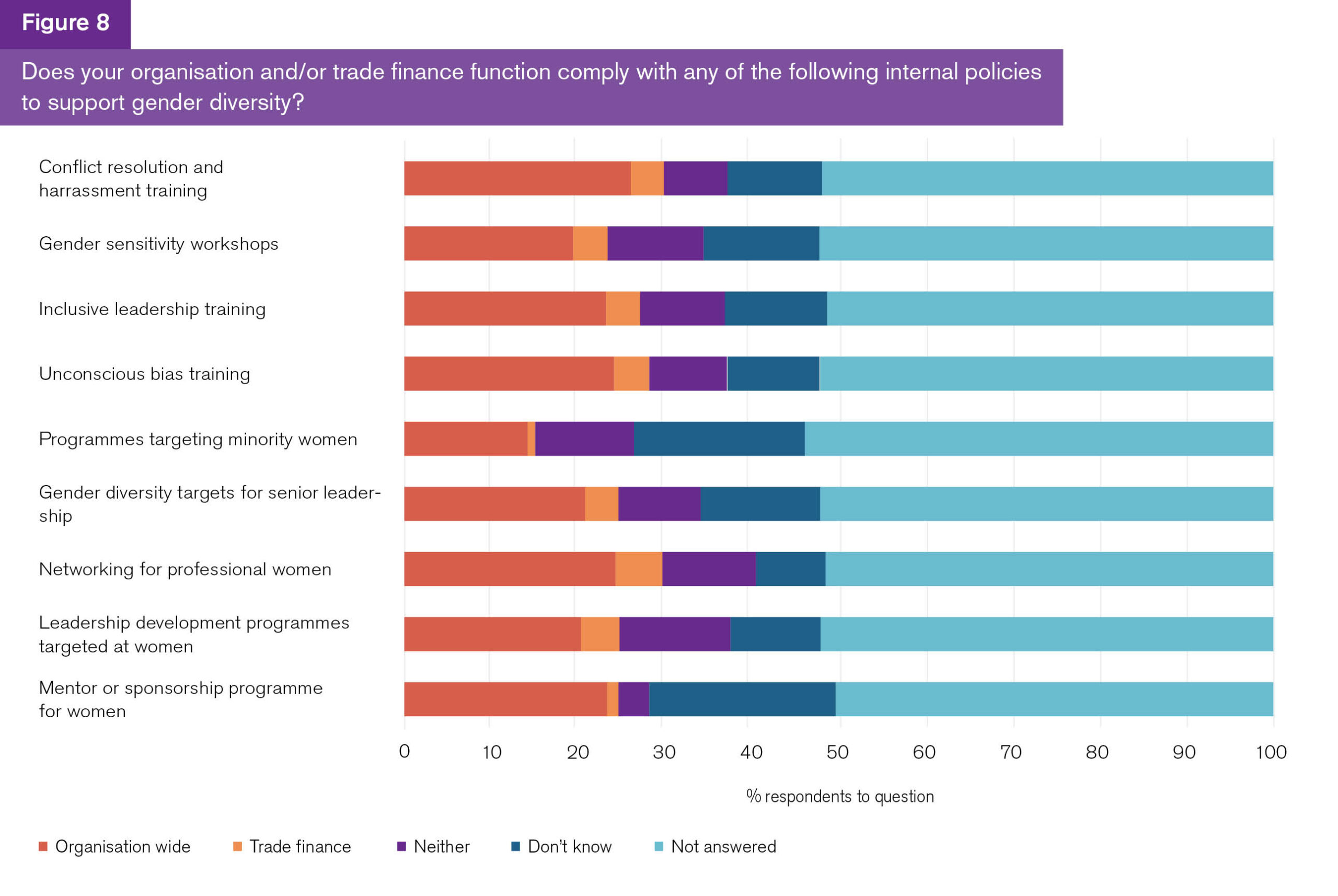

GTR: When it comes to internal standards, is there a similar lack of awareness of whether organisations are complying with internal diversity frameworks?

Harding: Yes, absolutely. What the data shows is that people either don’t know or are unwilling to say whether their organisation complies with its own internal codes of conduct.

That tells us something really important: if leaders within organisations aren’t clearly articulating what the regulatory or internal frameworks are, it leaves individuals without the tools they need to advocate for themselves. Their position is weakened, and their power to own or build their own diversity journey is undermined.

Of course, some organisations might respond by saying; ‘We do communicate all of this.’ But the data suggests otherwise. At the very least, the message isn’t getting through.

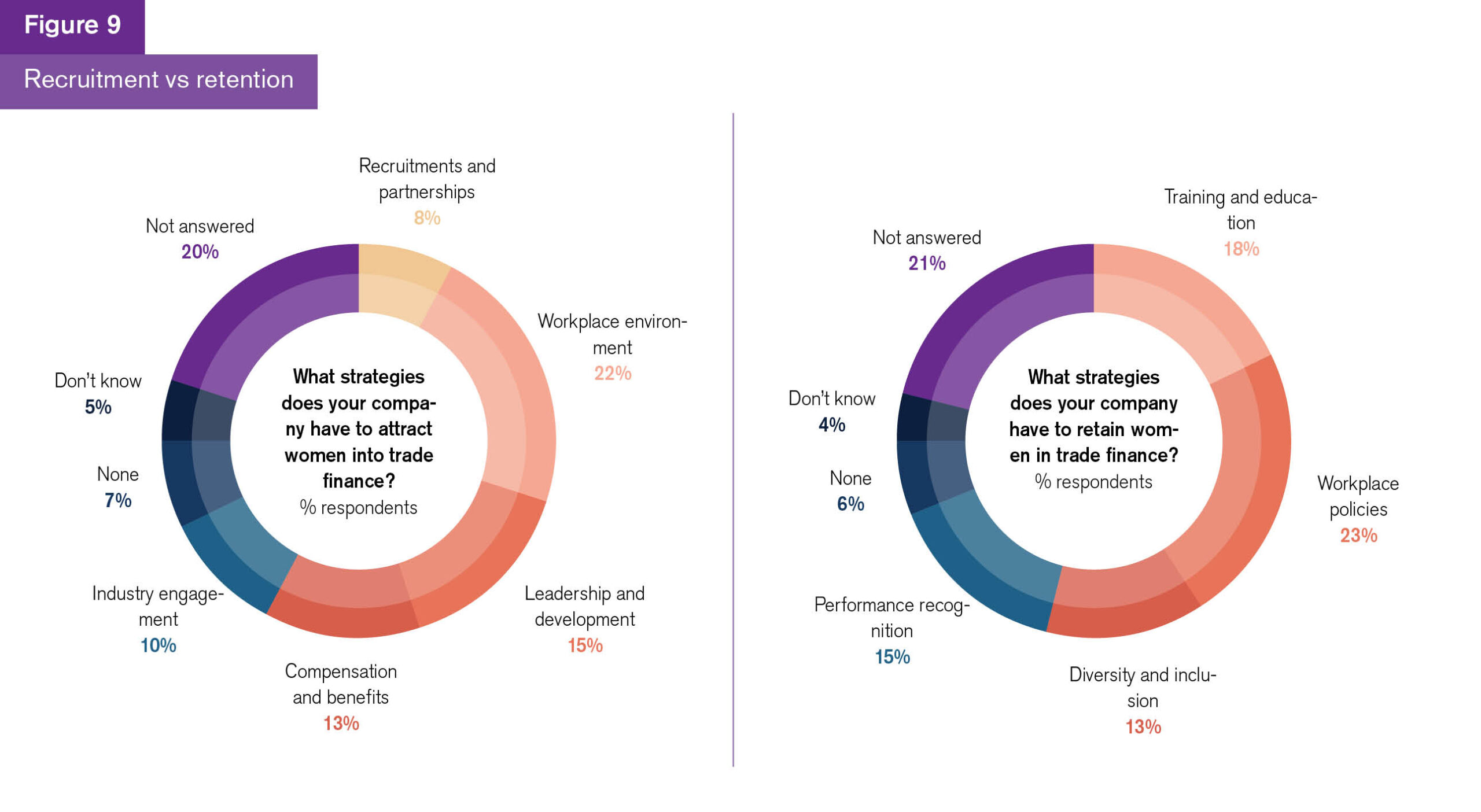

GTR: The survey also explored how companies approach attracting versus retaining women in trade finance. Where are organisations putting their energy?

Harding: The level of ‘don’t know’ responses is noticeably lower on this chart [figure 9] compared to others, particularly when it comes to recruitment and retention. That’s quite significant. It suggests that, both at the organisational level and within trade finance specifically, there’s a greater awareness of efforts in these areas. So in a way, this bucks the trend we’ve seen elsewhere.

While around 25% still didn’t know or didn’t respond, which is noteworthy, it’s much lower than the figures we saw for the more strategic or structural questions. That indicates people are more attuned to what’s happening when it comes to the practical aspects of recruitment and retention.

If you break it down further, several key areas emerge. Across organisations generally, workplace environment ranks highly. Within trade finance, workplace policies are particularly prominent. That aligns with the earlier point about lived experience – people are reporting a more positive experience of gender diversity in practice, and here we can see that reflected in what organisations are emphasising.

It shows that the focus on recruitment and retention is translating into tangible efforts, particularly around workplace environment and policy. That’s a meaningful shift.

Leadership also comes through strongly on the organisational side. And I think it’s important to remember that leadership isn’t just about those at the top, it’s about empowering individuals throughout an organisation. But the fact that so many people still don’t know about the broader frameworks in place suggests a communication gap. That undermines the effectiveness of leadership, because leadership is also about transparency and enabling others to act with confidence.

So while the data here shows some real positives, it also points to an area that still needs work – making sure the information and intent behind these efforts reach everyone.

GTR: Overall, what have we learned from this survey?

Harding: We’ve learned several things. We’re living in a rapidly changing world, and the pace of that change is really quite extraordinary. The conversation we’re having now is very different to what it would have been a year ago. There’s a new level of caution and complexity, and having data in this context is crucial. It reminds us that these issues still matter.

The good news is that, broadly speaking, people are having positive experiences when it comes to gender diversity, especially in terms of their day-to-day workplace environment. That’s a great start.

But there’s still so much more to be done. One of the things I find most striking, and frustrating, is the ongoing challenge of managing what economists call intangibles. For years, we’ve studied productivity in the workplace and found that if you manage these intangibles well – whether it’s gender, innovation, sustainability or social responsibility – the results are clear. These are the organisations that grow faster, are more profitable and have higher levels of productivity. They create environments where people want to contribute more. So why isn’t this a mainstream business conversation?

We still know that women are underrepresented in senior roles.

We still see widespread lack of awareness around gender parity policies and organisational strategies. That’s something that could be fixed quite easily just by communicating better. Awareness helps people feel part of something. It gives them the confidence to contribute, to speak up and to be part of a diverse, dynamic workplace.

So now the question is: where do we go from here?

Every person who’s taken part in this discussion is probably going away asking themselves: ‘Do I know if we have a gender diversity policy? Do we have a gender pay parity policy? Does my team know?’ That kind of self-reflection is important. Because change doesn’t start at the top or in a policy document. It starts when individuals begin to ask the right questions.